Research by inventory

Object research by inventory

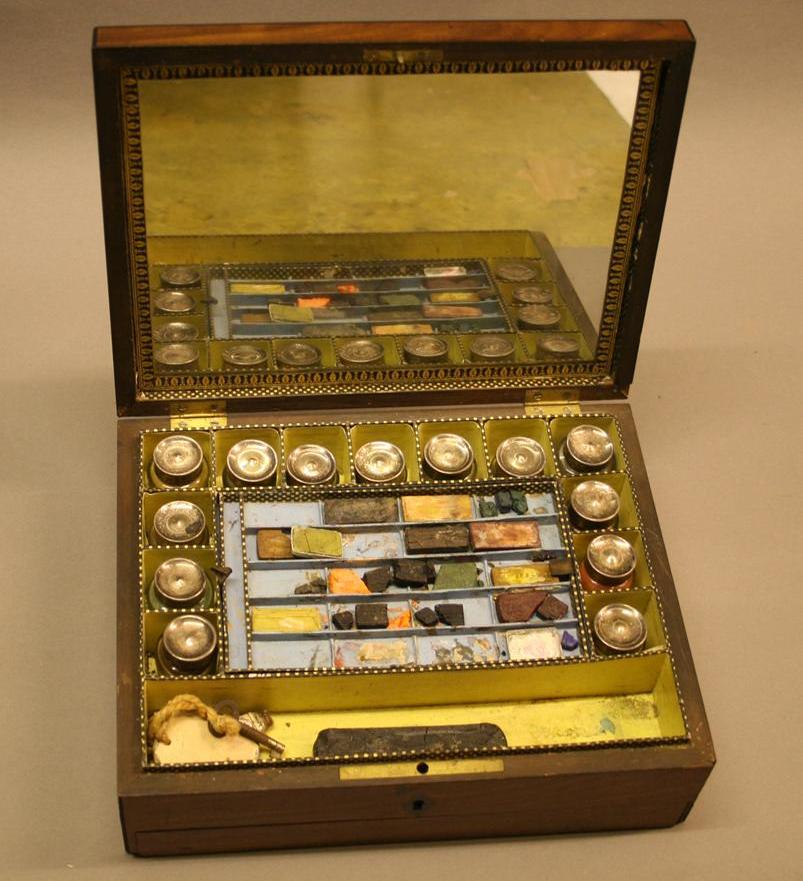

In the beginning the uninventoried object is just a simple object. The box with the gouache picture of the ancient goddess of hunting (Diana) on the lid (photo 1) arouses curiosity about its contents due to its elaborate design. After opening, a full paint box becomes visible (photo 2). Only one look into the access book gives the precious object from the beginning of the 19th century a history that leads into the depth of the collections of the Historisches Museum Frankfurt. According to the record, the paint box belonged to the Frankfurt decorative painter Johann Daniel Scheel (1773-1833). A first research shows stations of his artistic life. Born on 15 March 1773 as the son of a master button maker, Scheel received his training at the Düsseldorf Academy. A search in the database of the Historisches Museum Frankfurt leads to a landscape painting (photo 3) by Scheel. As further research shows, this is the work he produced as a member of the Frankfurt painters' guild to attain the title of master. A further painting in the collection also provides an insight into the life of this artistic personality. Scheel's second wife Johanna Rosina Scheel, born Silbermann, can be seen in a portrait that Peter Cornelius, a friend and artist colleague from Scheel's Düsseldorf days, painted (photo 4).Scheel's artistic significance lies in his work as a spatial artist. He created decorative paintings for the Tuscan Hall in the Würzburg Residenz, the Pompeian Hall in Schloss Homburg vor der Höhe, the banqueting hall of the Riedhof in Sachsenhausen of the Bethmann family and for a number of other country and garden houses of Frankfurt partrician families. This period of creativity can also be documented by the collection of the Historisches Museum Frankfurt. The Graphic Arts Collection contains a sketch for the middle hall of the Gogel country house from 1805 (Photo 5). The future will show what is still sleeping in the collections.

This small report of an inventory process shows that scientific inventorying involves much more than simply recording the existence of an object by assigning it a number: it involves classifying the object in a subject group, assigning it to an artist, a workshop or an industrial firm, dating it, researching previous owners, looking for possible modifications to the object after its creation, and often determining its authenticity. The inventory also includes an identification of materials and techniques and finally a determination of the condition, ideally in close consultation with the responsible restorers. The direct examination of the museum object can thus also contribute to the preservation of the inventory, if requirements are identified and conservation measures are initiated.

Only when this work of inventorying has been done can further museum work begin. The cataloguing of the inventory is a prerequisite for any further collecting activity and mediation. Only when it is known what belongs to the inventory can specific gaps be closed or, in the negative case, the growth of duplicate holdings be prevented. Only the classification of an object into a time period, into an artist's oeuvre or the allocation to a specific topic enables its integration into a historical and artistic context and thus into a planned exhibition. Nevertheless, inventorying is one of the often neglected and mostly unloved tasks in everyday museum work. It is extremely tedious and takes place in secret, without the glamour of the external effect. And this is quite wrong, because every exhibition is depending on a well inventoried and thus researched collection.