Main Panorama

The basement’s main theme is the river. Photographs and films from the 19th and 20th centuries, together with light marks, show the flood level. In the floor above, where the “toll office” was from the end of the 15th century, the theme is all about the history of Frankfurt’s economy and trade. Vivid objects create a lively impression of the connection between port and trade, toll and tax payments as well as the activities in the toll office.

Life on the river

With its abundance of fish, the Main was an important source of food for the inhabitants of the city, but also provided protection from invaders. As well as this, the waterway was a safe connection to the world and an important trade street. Fords and shallows, where the water was not much deeper than one metre, lead through the Main in Frankfurt. There, it was easily possible to cross the flat, slow-flowing river. It was only in the Staufer period that a bridge was built and connected to the city wall.

However, the river could become dangerous for the city’s inhabitants: strong flooding often posed a threat to the city. In winter, the Main often froze over. Ice drifts could then destroy the bridge and impede ship operation. The city also often experienced low water levels. As of 1883, the river was regulated, straightened, dredged and equipped with barrages. The waterfront in the city was fixed with new wharfs as early as the 1820s.

The Toll Tower

When the Main’s riverbanks were raised in the 19th century, the tower lost around three metres of its visible height. After the First World War, writer Fritz von Unruh lived in the tower. During the Second World War, parts of the tower burnt out and the distinct roof with its pinnacles was destroyed and the clockwork went missing. Following the war, the damaged pieces were re-built, staying true to the original. However, a suitable clockwork was first installed in 2012.

The Rententurm is one of only three remaining gate towers of the Gothic town fortification; the other two are the Eschenheimer Turm (1428) and the Kuhhirtenturm (1490) on the left bank of the Main.

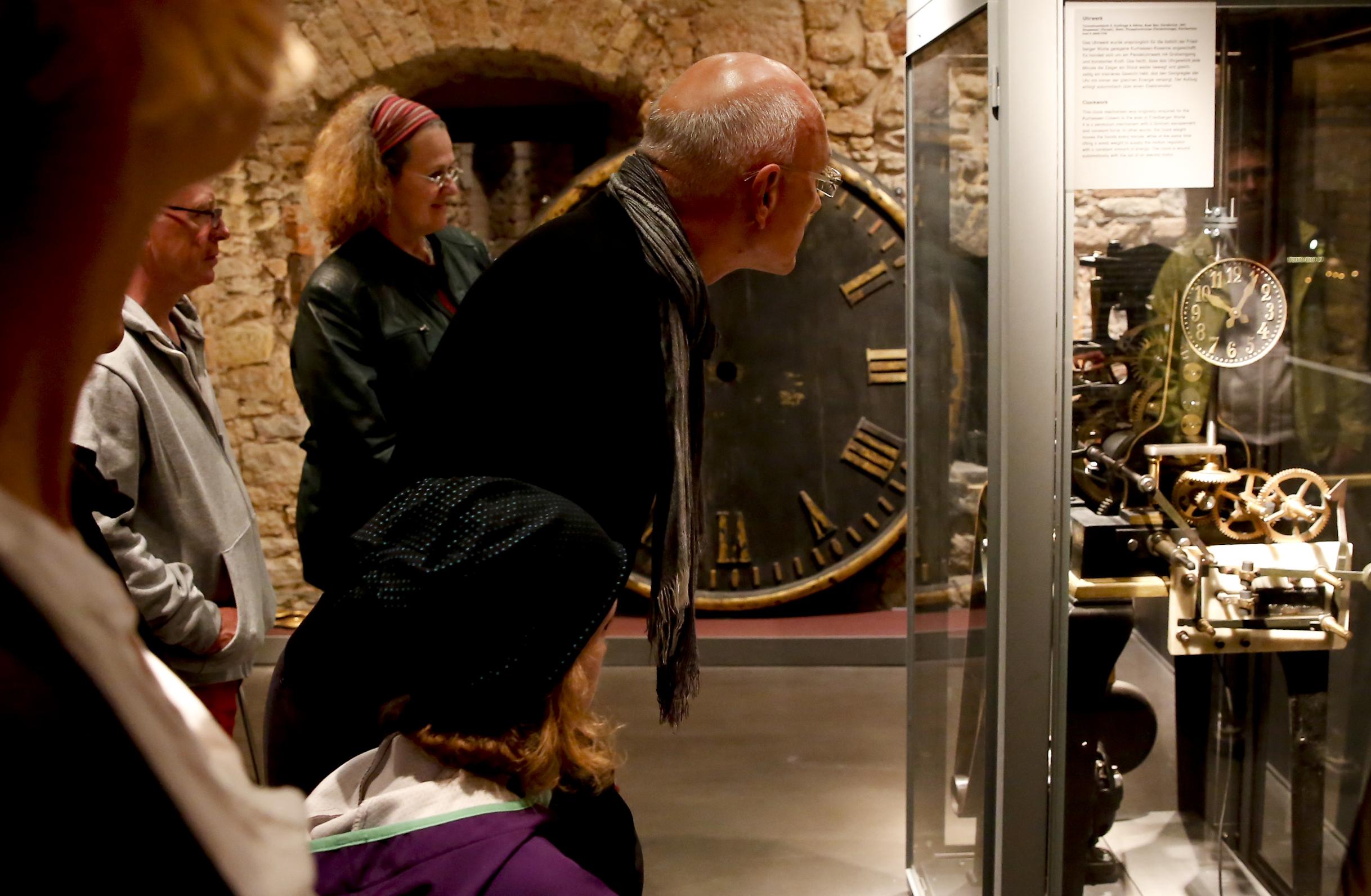

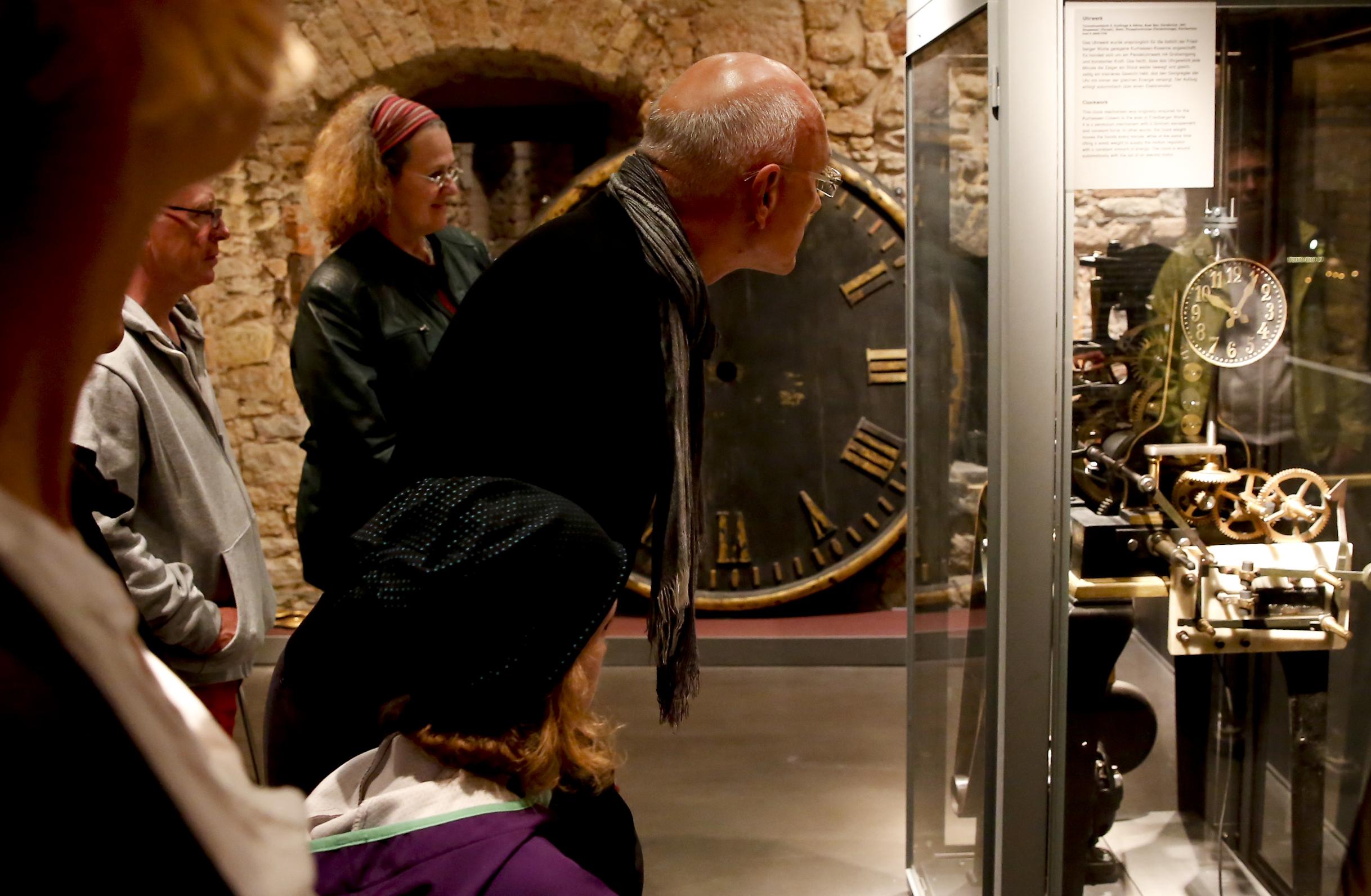

Time

In historic etchings, the appearance of the Rententurm is significantly characterised by the two black dials of the clock built into the tower. As part of the renovation of the museum’s old buildings, the clock was restored to give the Rententurm its characteristic appearance once more. The extent to which a reconstruction of the clock would even be possible was not clear from the beginning. Although the dials and hands of the clock had remained in possession of the museum, the clockwork was lost during the war.

Beautiful view

All goods that came to Frankfurt via the river or passed through the city needed to be declared here. Aside from this, indirect taxes and levies collected by the toll office were paid at the city gate (Fahrtor). These charges were mainly for the import and export of commercial goods. The most important of these was the wine that was delivered in large wooden barrels. Other goods subject to tax included other drinks, grains, crops and salted, i.e. cured, fish.

In 1383, the taxes collected by the “chest men” were recorded in the city’s civil code for the first time. This included the “Ungeld” – a consumption tax on wine, salt and different kinds of foods – that had to be paid by the seller. When wine, beer etc. was imported, the so-called “Niederlage” also needed to be paid; for exports, this was known as “Steinfuhr” – as originally, the carters had to also transport a load of stones for the municipal building authorities for every barrel of wine. In addition to this, there were taxes for using the port crane (“crane money”) and also bridge money at a later date. The exact amount of the taxes was determined in 1727 by imperial commissioners during the Frankfurt constitutional conflict and published in a printed schedule of charges. The taxes were collected in boxes and brought to the audit office once a week. Other customs offices were located at the Alte Brücke (Iron Bridge) and at the Affentor, the Friedberger Tor, the Eschenheimer Tor and the Bockenheimer Tor. During trade fairs, the Leonhardstor and the Metzgertor at the Main riverbank were also used.

The worst flooding in the last millennium was experienced by Frankfurt on the feast day of Mary Magdalene on 22 July 1342. A water level of 25 Rhenish feet was recorded at the city gate (Fahrtor) – the equivalent of 7.85 m today. The city was flooded for miles around. In the Weißfrauenkirche (previous location: Hirschgraben at the corner of Berliner Straße), the water measured around seven feet high, approximately two metres. The high-water mark originates from this church, which is no longer to be seen today.

The Main Riverbank at the City Gate

Friedrich Wilhelm Hirt (1721—1772) was famous for his small, elaborate staffage figures. These had already impressed viewers before the picture “Das Mainufer am Fahrtor” (The Main Riverbank at the City Gate) was even commissioned. It was always large-format landscape paintings that he enriched with these. This means that many friendly scenes can be discovered in the Frankfurt panorama as well as in a Wimmelbilderbuch (hidden picture book). Hirt’s painting was commissioned by Duke Anton Ulrich of Sachsen-Coburg-Meiningen. It was supposed to give the latter a view of the colourful Frankfurt life while he was residing in Meiningen. It is possible that he recognised individual people and personalities in the faces and types of Frankfurt society depicted in the painting. For today’s viewers, the artwork captures life in the city on the River Main in the 18th century. It is fortunate that the Duke commissioned it, as Hirt did not paint him a realistic view of Frankfurt’s Main riverbank, but rather combined the extraordinary and significant in his composition. Even its format hints at its importance: it is the largest view of Frankfurt am Main that was painted in the 17th and 18th centuries. In this work, the artist did not use the already characterised view from the west nor the equally refined view from the east. Only the unusual, unique view to the south allowed Hirt to capture the transhipment point at the port whilst doing justice to its significance. He expanded the area at the city gate (Fahrtor) into a stage. It provides the backdrop for a depiction of the practices of the time.