Hardly an ordinary life. Stories of work, migration and family

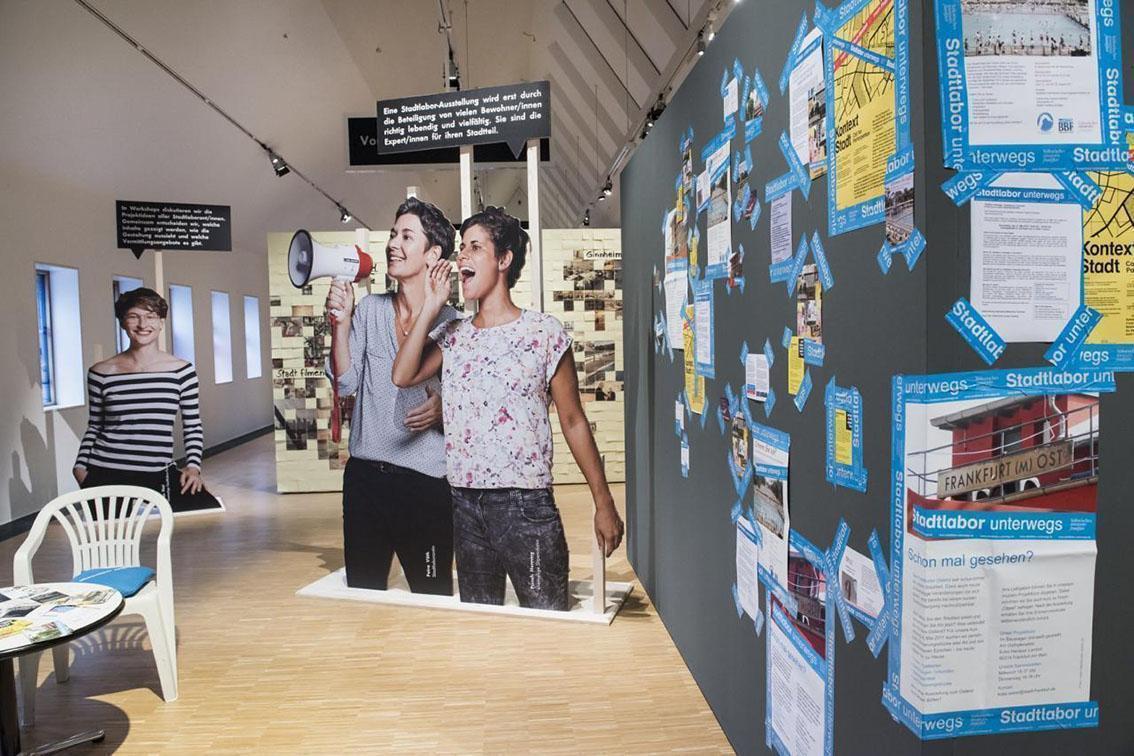

CityLab Exhibition

28 November 2019 - 5 April 2020

28 November 2019 - 5 April 2020

Migration is the standard case of history. All societies are essentially shaped by migration histories. In Frankfurt today, more than half of the population has a so-called "migration background," and among children it is even more than 70 percent. Nevertheless, migration history is still not a self-evident component of the German collective memory. With the CityLab exhibition "Hardly an ordinary life. Stories of Work, Migration and Family," we brought the experiences and memories of migrant workers into the spotlight, from the "guest workers" of the 1960s to the "expats" of the present day.

Impulse for the exhibition

The idea for "Hardly an ordinary life" was already formulated in 2017 at the CityLab "Collection Check: Collecting Migration Participatively". Many participants of the CityLab at that time belong to the second generation of immigrants, whose parents came to Germany mainly as "guest workers". They formulated the wish to articulate and record their specific experiences in an official memorial space such as the Historisches Museum. These ideas gave rise to the CityLab "Hardly an ordinary life".Labor migration - from the time of the guest workers to the present day

In cooperation with the museum team, the CityLab assistants developed seven contributions that showed how work and migration shape and change family life. Additionally, two artistic installations were created. All contributions dealt with different phases and epochs of recent migration history, from the so-called "guest worker era" to the present.Recounting migration history

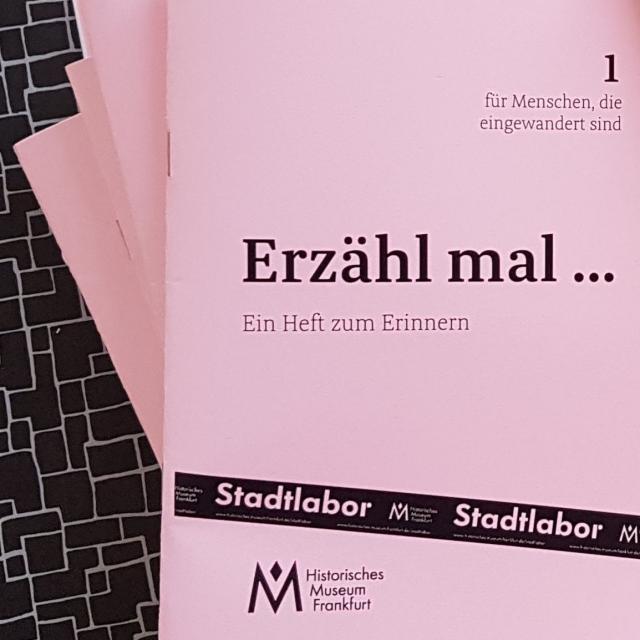

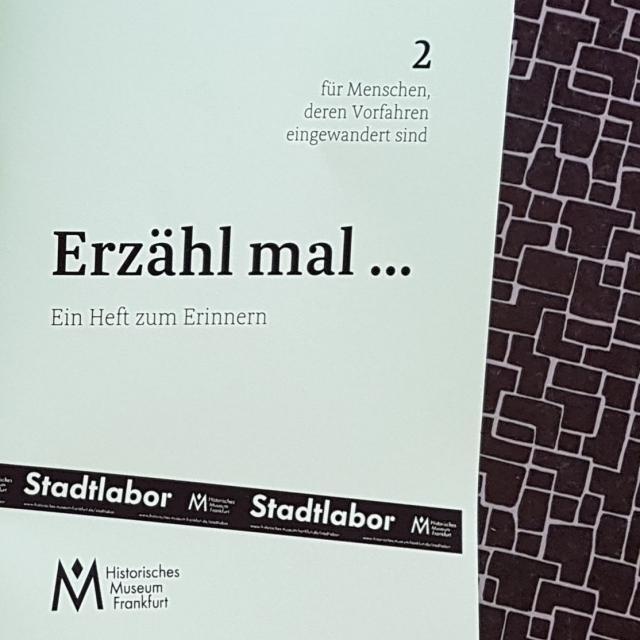

The exhibition presented around 70 individual stories and wanted to encourage people to tell their own (migration) stories or to have their stories told by friends, colleagues or relatives. In the exhibition, we invited people to sit down on two armchairs with a view of the Main River and tell their stories. Two story coloring books were available as conversation starters. These notebooks could also be taken away by the visitors. These booklets were very popular and can be downloaded here (materials, see below). In the supporting program, storytelling cafés, workshops, guided dialogues and intersectional generation dialogues offered numerous opportunities for exchange.More about the individual contributions

The "Frankfurt Stories" spotlighted 15 Frankfurt residents who came to the city as migrant workers. The enormous range between precariously employed and sought-after specialists was revealed. The short portraits clearly revealed the linguistic, structural and emotional difficulties migrants are confronted with. However, the view towards self-organizations or potentials was also opened up. How migration is remembered, which images have entered our collective memory, was reflected on four media machines that presented films, photographs and audio recordings as well as concepts and statistics.

Sewastos Sampsounis also addresses the experience of separation from parents in his contribution "Suitcase Monument". Unlike Olcay Acet, he chooses the term "suitcase child" for himself. This controversial term refers to children of the first generation of guest workers who were left behind in their countries of origin or who commuted back and forth between Germany and the sending countries. In his installation, which shows a suitcase on a pedestal, the suitcase is also staged as a symbol of guest worker migration, as a "guest worker monument". The suitcase is a museum item without a specific history, which Sewastos Sampsounis came to know in the context of the Collection Check. In "Hardly an ordinary life" he invited the visitors* to give the suitcase a story. More than 70 stories were submitted and presented in the exhibition.

Tamara Labas conducted interviews with children and grandchildren of "guest workers" for her contribution "root case stories". She worked out how the migration history of their ancestors shaped their own lives and experiences. Loneliness and pressure to adapt were two of the central motifs. The interviews were transcribed and presented in artistically designed booklets that have become part of the Library of the Generations, where they can still be accessed.

In the contribution "My family in the river" by Ibrahim Aydin, students of the Turkish language class presented their families, organized across national borders. Language is an important tool for maintaining family relationships. With his contribution, Ibrahim Aydin also emphasized that multilingualism is an important and still underestimated resource, especially with regard to Turkish-speaking children.

What do young people know about the migration history of their parents or grandparents? What role does this history play for them? Olcay Acet explored these questions in the contribution "Voices of Migration". The young people were guided to prepare and conduct interviews and to cut them for the exhibition. These were presented on old telephones.

The research-based artistic work by bi'bak "Bitter Things - Narratives and Memories of Transnational Families" addresses family separation through labor migration with a focus on the - often bitter - things: sending gifts is a common practice within transnational families and yet cannot compensate for the closeness of parents and children. The project bridges the gap between the so-called guest worker era and the present; today, most migrant workers in Germany are employed as caregivers, in elder care or childcare.

Alteration tailors

Sema Yilmazer drew the attention of the CityLab to the barely noticed field of work of alteration tailors in Frankfurt. Since the 1960s, more and more of these businesses have been run by "guest workers" who have taken the step from wage dependency to self-employment. In the exhibition, three film portraits of tailors were presented, which recounted the advantages and disadvantages of self-employment: It allows free time management and thus also the compatibility of work and family. But it is often also the only way to earn money if you cannot find a job because your qualifications are not recognized or because of labor regulations. And as an entrepreneur, you also bear the entire risk for your own existence.The perspective of children

Five of the nine contributions revolved around the experience of children and young people. Olcay Acet's artistic installation "Generation One-Comma-Five" focused on Turkish children who grew up separated from their parents. The recruitment agreement between the FRG and Turkey excluded family reunification, so that many children grew up in the care of relatives. In the video portraits, adults - the children of that time - report on what consequences the separation experience had for them. Their work is intended to help bring into focus the scars of being left behind and not being able to settle in. Olcay Acet states that these experiences have not yet become part of the collective memory, although at least the Recruitment Agreements are recognized as part of German history.Sewastos Sampsounis also addresses the experience of separation from parents in his contribution "Suitcase Monument". Unlike Olcay Acet, he chooses the term "suitcase child" for himself. This controversial term refers to children of the first generation of guest workers who were left behind in their countries of origin or who commuted back and forth between Germany and the sending countries. In his installation, which shows a suitcase on a pedestal, the suitcase is also staged as a symbol of guest worker migration, as a "guest worker monument". The suitcase is a museum item without a specific history, which Sewastos Sampsounis came to know in the context of the Collection Check. In "Hardly an ordinary life" he invited the visitors* to give the suitcase a story. More than 70 stories were submitted and presented in the exhibition.

Tamara Labas conducted interviews with children and grandchildren of "guest workers" for her contribution "root case stories". She worked out how the migration history of their ancestors shaped their own lives and experiences. Loneliness and pressure to adapt were two of the central motifs. The interviews were transcribed and presented in artistically designed booklets that have become part of the Library of the Generations, where they can still be accessed.

In the contribution "My family in the river" by Ibrahim Aydin, students of the Turkish language class presented their families, organized across national borders. Language is an important tool for maintaining family relationships. With his contribution, Ibrahim Aydin also emphasized that multilingualism is an important and still underestimated resource, especially with regard to Turkish-speaking children.

What do young people know about the migration history of their parents or grandparents? What role does this history play for them? Olcay Acet explored these questions in the contribution "Voices of Migration". The young people were guided to prepare and conduct interviews and to cut them for the exhibition. These were presented on old telephones.

The research-based artistic work by bi'bak "Bitter Things - Narratives and Memories of Transnational Families" addresses family separation through labor migration with a focus on the - often bitter - things: sending gifts is a common practice within transnational families and yet cannot compensate for the closeness of parents and children. The project bridges the gap between the so-called guest worker era and the present; today, most migrant workers in Germany are employed as caregivers, in elder care or childcare.