bought. collected. looted? Everyday Objects and their Nazi Past

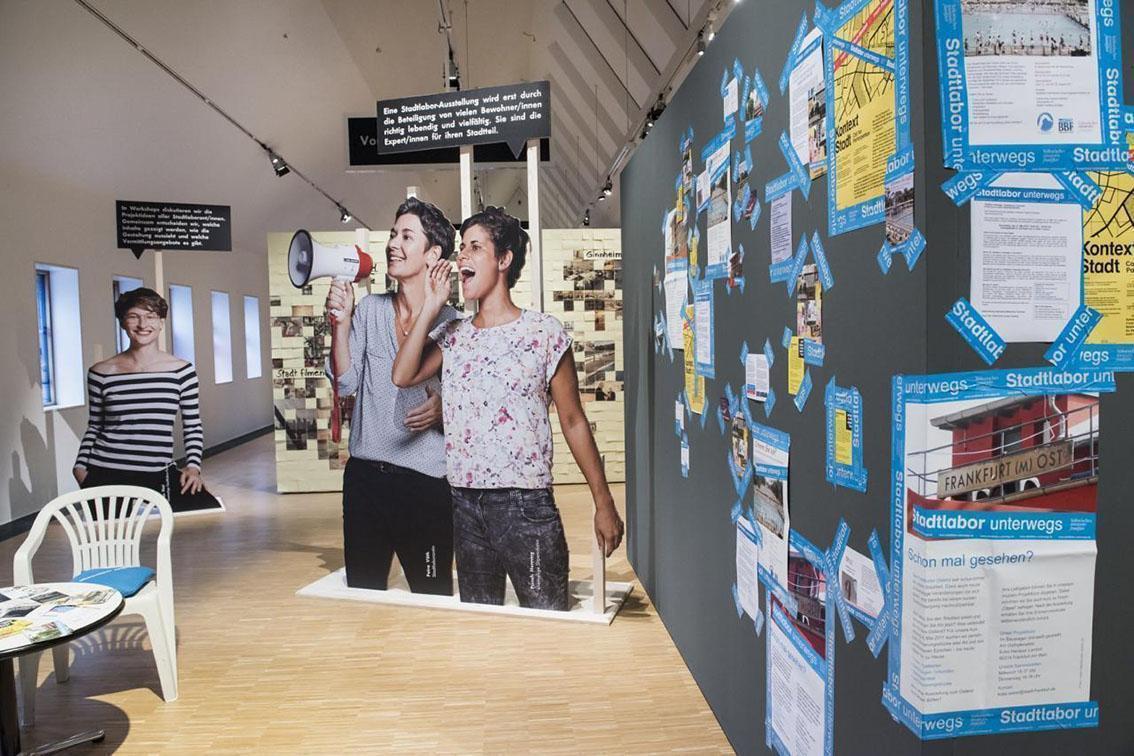

A City Lab exhibition in connection with the travelling exhibition “Legalised theft”

From May to October 2018, the City Lab was studying “difficult things”, i.e. engaging with objects previously owned by Jews, the ownership of which changed in the period of National Socialism. This City Lab was connected to the travelling exhibition “Legalised theft. The treasury and the looting of Jews in Hessen 1933-1945”, developed by the Fritz Bauer Institute and theHessischer Rundfunk . The exhibition had toured Hessen for 16 years and now came to a conclusion at the Historisches Museum, where a selection of more than 150 cases was exhibited which have been researched at the various exhibition locations since 2002.

Traces of “legalised theft” at the museum

The final presentation of the travelling exhibition was used by the Historisches Museum as an opportunity to demonstrate the traces of “legalised theft” that are still visible today: in the museum collection and in private ownership. Therefore, the exhibition “Inherited. Bought. Stolen?” was also developed to supplement this. Part of the exhibition was used to show how the museum profited from “legalised theft” from Jews, what role provenance research plays in the museum and which questions and difficulties it encounters. In the second part, the effects of “legalised theft” on six families were explored, whose stories are told in the Bibliothek der Generationen.

“Difficult things” City Lab

The City Lab explored objects in private ownership, the owners of which changed during the period of National Socialism, e.g. at public auctions where the belongings of deported Jews were sold. People whose homes had suffered bomb damage who received new clothing and furniture were often provided with items that had previously belonged to Jews. Countless items changed hands in this way and lots of people, both museums and individuals, profited from this “legalised theft”. Other “difficult things” that were shown in the City Lab were “souvenirs” of Wehrmacht soldiers that were brought home from “occupied territories”, e.g. icons, a silver tumbler, linen and jewellery. In what circumstances did these things change hands?

Traces of the expropriation, persecution and murder of Jews under National Socialism are still visible now in our “world of things”. At the start of the “Difficult things” City Lab, the following questions were asked: Where are all the things that were sold under duress, seized, sold and stolen now? Do we still have them? For the 2018 City Lab, we searched for everyday objects of Frankfurt residents that were previously owned by Jews or came from “occupied territories”. Lots of families have these “difficult things”. Only fragments of their story have been passed down. There are allusions and rumours. The objects are surrounded by secrets. We ask questions. Why is there an auction ticket on grandma’s piano? How are grandparents whose homes were bombed passing on antique furniture, table linen or silver cutlery? A total of nine people were involved in the City Lab and presented their “difficult things”, making their questions and doubts about the provenance of the items public. The City Lab looked for answers to these questions. In the usual participative manner, we attempted to shed light on the history of the objects and their previous owners.

In cooperation with the Fritz Bauer Institute, a series of workshops was developed that included, for example, an introduction into the methods of archival research. People who own “difficult things” were provided with support in their investigations into everyday objects or family histories by the historian Ann-Kathrin Rahlwes and the archivist from the Fritz Bauer Institute, Johannes Beermann. The results of the archival research were discussed in a confidential environment. The “Difficult things” City Lab had a total of nine participants. For lots of participants, engaging with the “difficult things” was an opportunity to look at their own family history and start conversations about the involvement of their own ancestors in the National Socialist period and how this was dealt with in the post-war period. And, even if it was not always possible to find out about the history of the objects in question, the search itself became the subject of the exhibition, as a form in which to engage with difficult aspects of the period after National Socialism.